Your cart is currently empty!

Everyday Spaces of Greenwashing

Enzo Lara-Hamilton

Greenwashing is a burgeoning form of deception in Australia. Where an environmentally sustainable product or practice is one that supports and sustains natural ecological systems, greenwashing is the imitation of sustainability—superficially adopting the aesthetics of ecology.

Companies market their products in a cute green vest of sustainability, despite their product or practices being deeply unsustainable. This makes ethical consumption difficult for eco-minded people, requiring significant work to fact-check, decipher and uncover the truth behind green-clad products. The expansion of greenwashing makes corporate Australia appear evermore virtuous, whilst it evermore destroys.

We exploit less: this is the subtext between the lines of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) reports, symptomatic of the economic system designed to extract from and exploit environments and peoples. Capitalism recuperates revolutionary ideas and symbols, extracting what is profitable 1. In the context of environmental sustainability, companies co-opt sustainable aesthetics only to further profits. Often the most sustainable thing a company could do is not exist, however this is out of the question. Company values are usually a spin on the Triple Bottom Line: ‘People, Planet, and Profit’. Unfortunately, when profit calls for the exploitation of people and the planet, a company will choose the former for its continued existence.

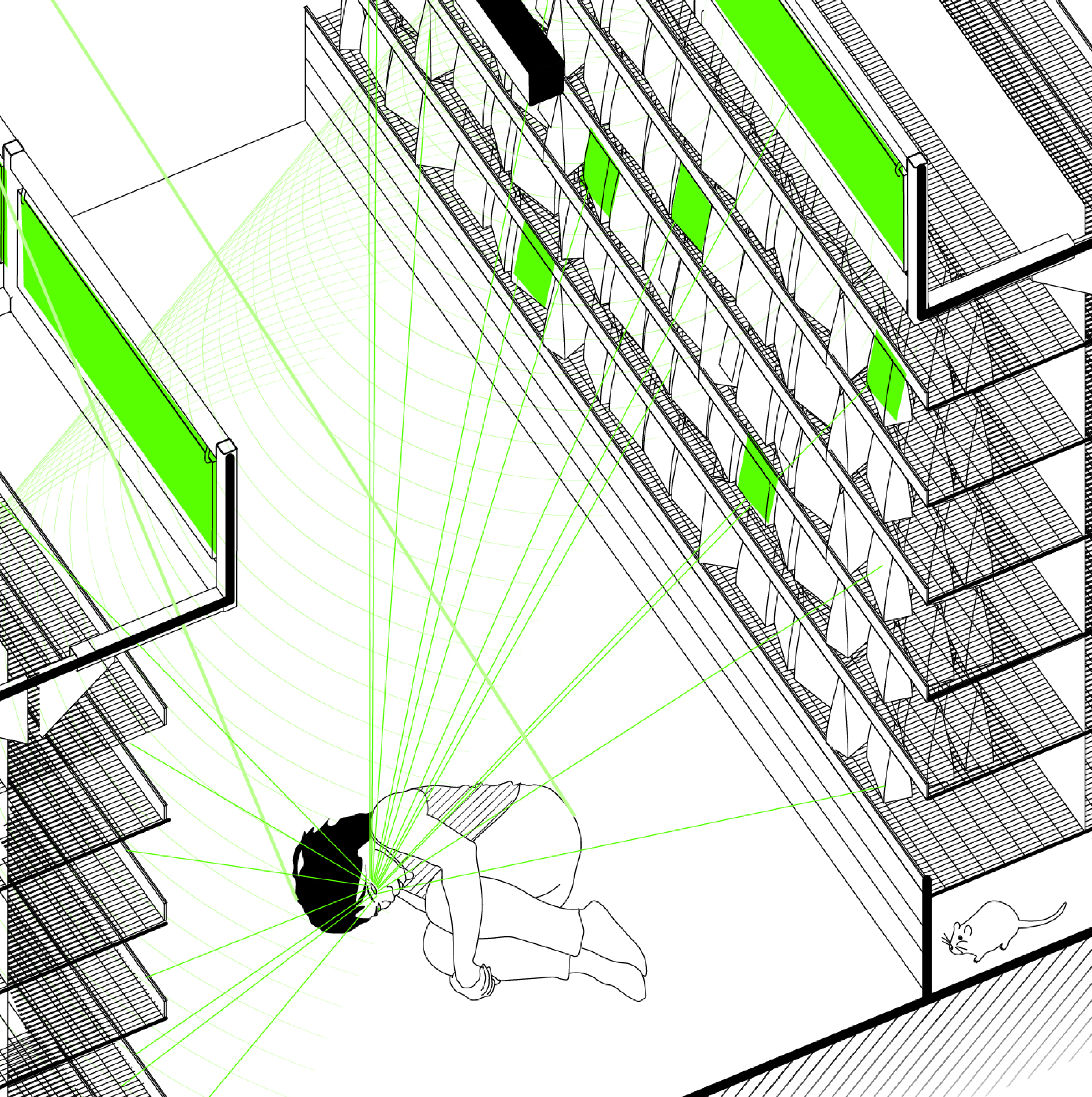

Profit not only produces false marketing strategies, but it also drives the production of new spaces.Greenwashing occurs within these spaces, now retrofit with eco-friendly aesthetics and features. To resist greenwashing, we who have the means need to resist the marketing strategies as well as the spaces faux sustainability occur in.

Everyday Spaces

Spaces like supermarkets, office buildings, or digital worlds all strengthen the success of greenwashing. These are everyday spaces, with their features usually unacknowledged, theatres for our lives. Yet it is here where greenwashing continues to develop, outside of green marketing visuals into the spaces we inhabit.

Features of these spaces range from hiding supply processes, oversaturating vision, to using fake materials or shadow-profiling. All these features frame greenwashed products positively or obscure our ability to see their real impacts. Poor, quick or lack of sustainable choices caused by these spaces often lead to continued ecological destruction.

Space is produced, but by and for whom? Spaces of our everyday existence are largely constructed to increased consumption and profit. If so, the materials, signage, and spatial organisation will be produced, now changing just enough to appear sustainable. Spaces are not apolitical. Just as a wall enables segregation, or absence of a public toilet enables street defecation, a space of greenwashing enables the continued destruction of the biosphere. Knowing how spaces help greenwashing will allow eco-minded people to properly interrogate claims of sustainability and how they are being influenced. The alternative is the continued slurping of Keep-cupped™-Brazilian-monocropped-iced-soy lattes with metal straws while the world continues to burn.

… You’re greeted by The Fresh Food People’s piercing green halogen symbols. They harshly sear your retinae, simultaneously reassuring you that green and fresh is gospel. You enter. A polished, plastic-packeted punnet of raspberries, paper straws and sustainably-fed beef scream for your attention among the omni-coloured combinations of other aggressive packaging, a silent Pachinko parlour assaulting the core of your being. As Katy Perry’s Firework (2010 radio-edit) pummels your ear drums into submission, youreach for the pesticide coated, GMO monocrop Granny Smith you grew up on, picked by exploited migrant workers for $8 an hour. Your supple, docile body, constantly surveilled, must gather soft plastic wrapped imported tofu and organic solanato™ tomatoes in a plastic wrapped cardboard tray for your survival. Your experience is shared across the continent. With 995 fresh spots across Australia, Woolies turn over $4.44 billion in sales to give you their ‘sustainable’ experience crooned by Jamie Oliver’s soothing British mumbling.

Keep calm and carry on…

Supermarkets

Supermarkets employ tactics that increase consumption of greenwashed products by producing spaces where people feel comfortable purchasing such products, believing they are not damaging the environment. Australian supermarkets like Woolworths, Coles, and Aldi’s create greenwashing opportunities in several ways, some relying on larger urban organisation. One such factor is displaced production: 66% of Australia’s population live in urban areas 2 , detached from the sites of extraction required for their consumption. This displacement is not limited to the supermarket and is a significant geographical strength of greenwashing practices. Rarely are we compelled to imagine the specifics of our consumption. A whiff from a BP petrol pump is never associated with the screams of sea life. Yet the bursting of whale eardrums by 260dB seismic testing is a common practice in the search for oil (Figure 1.1).

Supermarkets also give you countless options. For Almond milk alone, you could choose Vitasoy, Australia’s Own, Pure Harvest, Bonsoy, Almond Breeze, Inside Out, So Good or Homebrand Woolies Almond milk. Oversaturated imagery and information make decoding a product difficult. Gloria Phillips-Wren suggests information overload results in cognitive strain, stress and lowers decision making quality3. Making through decisions with cognitive strain is difficult, when green labels present themselves, the easiest option is to assume they are better than their non-green counterpart. Figure 1.2 shows half an isle of Woolworths Macro section with over 600 products presented. The clumped sections of specials and dispersed distribution of green products provide points of visual focus, within an overwhelming sea of symbols. This overloaded, partially sustainable looking context means decoding a product’s eco-friendliness is hindered in supermarkets, increasing the effectiveness of greenwashing.

Natural materials and decals work toward strengthening sustainable brand imagery. Timber storage, wooden barrels, corrugated cardboard, brown recycled paper, and hessian fabric all contribute to a sustainable aesthetic. Printing image textures of these ‘sustainable-looking’ materials have also been adopted across supermarkets, Woolworths being particularly strategic. Using symbols that are associated with low impact local markets create an impression of environmentally low impact production. Particularly, Hessian sacks and wooded barrels are used for displaying small amounts of fruits and vegetables in Woolworths. Printed image textures particularly wood grain is applied onto plastic vinyl and steel materials. These deceptive gestures of natural materials, much like fake plants, legitimize using symbols of sustainability without being sustainable. Greenwashed packaging found in supermarkets uses the same tactic on a smaller scale. Both change our perceptions of sustainability to a symbol-based engagement, rather than thinking beyond this, to the hidden life cycle of the items and spaces.

Office Buildings

Sustainable buildings can be co-opted by highly unsustainable companies for green promotion. (Figure 2.2) Australia has two main building rating systems NABERS and Green Star, which are used to verify a buildings environmental impact, though not the companies therein. The NABERS (National Australian Built Environment Rating System) rating system measures energy, water, waste, and indoor environments. Greenstar has 8 main categories to assess a building’s impact, though oddly, some projects have achieved world leading ratings without a single tree being retained or planted. Both rate projects out of 6 stars. These two systems are important for the Construction industry and are crucial in driving country-wide shifts toward sustainable buildings and precincts. The challenge for sustainable office building is to prevent unsustainable companies justifying their operations within them. Both Shell and BP’s headquarters in King Square, Mooro (Perth) and Docklands, Naarm (Melbourne)respectively has 5 and 4.5 star NABERS energy ratings. This is despite Shell accounting for 1.6% of the global carbon budget from 2018-2030 and only dedicating 1% of its investments in low-carbon energy sources. BP, in 2019 pledged to reduce fossil fuel investment despite increasing acreage for new exploration access by 58,000 km2 in the same year 4. Acknowledging ecological impacts of companies in buildings should always be considered in building calculations, as to resist the frequent co-option of such green spaces.

Rebuilding a green-certified building when owners should sustainably retrofit the existing buildings is a form of greenwashing. Upgrading an existing building (also known as retrofitting) such as a poorly insulated, energy intensive clothing store is significantly more sustainable than demolition and rebuilding it (Figure 2.2) . In the eyes of developers and property investors, retrofitting is not as beautiful, and often not as profitable. A case in London of an ‘Outstanding’ BREEAM UK environmental assessed new build would contribute 40,000tCO2 required for its completion. The proposal required the demolition of the existing building which could have been retrofitted, saving significant carbon and costs 5 . Demanding the more sustainable option requires challenging the necessity for a new recycled project, when it is better to reuse what already exists. New offices and buildings that are highly sustainable might still be hiding a lower impact decision, despite promoting an ‘outstandingly’ sustainable building.

Digital Spaces

Technology companies use shadow profiles, allowing companies access to audiences that will buy greenwashed goods and services. Browser tracking is almost ubiquitous on the internet. 75% of the top 100,000 websites use Google Analytics6, meaning your data and a profile can be created using your cookies, even if you have no affiliation with Google. Targeted marketing can then coax you into buying a sustainable looking product, particularly effective when Instagram advertises between every 4 -5 posts. Whispering ‘sustainability’ five times into a smartphone provides ads for bio-degradable business cards, stone paper, a recycled plastic planter, a thermal label printer with biodegradable labels, and a recycled ocean plastic watch that donates 15% of proceeds to Sea Shepherd. The experiment suggests that curated marketing for shadow profiles will always drive further consumption, rather than promote reduction or reuse. Not all products above are useless, but all require spending money to obtain an individual sense of sustainability. Again, greenwashing can sometimes mean the creation of a new product that is sustainable but unnecessary.

Natural environments are digitized, filtered and reduced by phones, aiding greenwashing’s effectiveness. Phones provide a steady flow of photographs and symbols of natural environments. These representations of nature are employed actively by greenwashing companies. Images of natural environments, be they photographs of Eucalyptus trees or Instagram-filtered sunsets, reduce real phenomena into pixels. Backlit, they symbolize and reduce a real, complex ecology. Greenwashing thrives on simulacrum of nature; a phone enables this. Appropriating lush forest imagery or the perfect shade of green, companies promote consumption of a product with no verification of the product’s impacts on the environment.

…

Greenwashing is strengthened by the spaces that curate consumption. Supermarkets, Office buildings, and Digital spaces all have features that drive greenwashing. Spaces are never just physical forms, rather political and at times ecocidal spaces enabling faux sustainability. Being eco-minded means continually reminding yourself of the impacts you have on the planet and avoiding illusory sustainable signalling. A supermarket is the backdrop to your daily practice of buying food, plastic imagery and overmarketing obscure truth, priming you for greenwashing. An office building can be the symbolic greenery that convinces you of a business’ credibility. A digital screen can coerce you into purchasing any number of sustainable sounding products you didn’t quite need.

Being eco-conscious, we should continually be aware of, call out and move away from these spaces if or where possible. Spaces can lead to ecological destruction, but they can also heal, connect, and improve environments. Local markets, op-shops, books, face-to-face connection, protesting and consulting friends or the internet can all shift us away from greenwashing practices toward sincere existence. This in turn demands and creates new spaces that are honest and wholistically sustainable.

1. Wark, McKenzie (2008) Fifty years of recuperation: the Situationist International. Princeton Architectural Press

2. 2021 Census Data https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/people-and-communities/location-census/latest-release

3. Gloria Phillips-Wren & Monica Adya (2020) Decision making under stress: the role of information overload, time pressure, complexity, and uncertainty, Journal of Decision Systems, 29:sup1, 213-225, DOI: 10.1080/12460125.2020.1768680

4. Li M, Trencher G, Asuka J (2022) The clean energy claims of BP, Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell: A mismatch between discourse, actions and investments. PLoS ONE 17(2): e0263596. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263596

5. Hurst, Will (Jan 2022) New carbon report slams Pilbrow’s Oxford St demolition plans https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/news/exclusive-new-carbon-report-slams-pilbrows-oxford-st-demolition-plans Architect’s Journal

6. UK Government Dossier on Shadow Profiles (2019) https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5e1c4985e5274a06b7450a13/Oracle_-_Response_to_SoS_-_Appendix_4_-_Google_Shadow_Profiles.pdf

Also see:

https://thefifthestate.com.au/innovation/design/australias-greenest-buildings-arent-actually-green/

https://www.clientearth.org/projects/the-greenwashing-files

Enzo Lara-Hamilton is a Naarm-based Space Cowboy trained in Architecture. His work focuses on ecological sustainability, resistance and the creation of ficto-critical worlds.