Your cart is currently empty!

Encountering the Spectre of Collapse: Bringing Marxism and Gaelic Animism into Constellation

Colm McNaughton

‘Thóg sé breis is cúig chéad bliain an aiste seo a scríobh.’[1] / ‘This essay has taken more than 500 years to be written.’

‘The old world is dying, the new world struggles to be born; now is a time of monsters.’ Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937).

We live in uncertain and potentially apocalyptic times. When I evoke the notion of apocalypse, I am drawing on its etymological root in Greek rather than the popular (mis)use of the term. In Greek, the word apokalupsis / ἀποκάλυψἡ, means ‘to uncover’ or ‘unveil’ as in something pertaining to the truth. Through the fundamentalist misreading of the book of Revelations from the Christian Bible, the word has come to mean ‘end times,’ ‘total destruction’ and ‘end of the world.’ This later (mis)reading is often grounded in an attempt at trying to control others through fear. In using the word apocalypse in this considered manner, I am trying to access the potentially healing, transformative and liberatory elements that are contained in its original truth-seeking mission. One way people are trying to make sense of the uncertainty and tumult presently being experienced is the underdeveloped, and sometimes hysterical, notion of collapse. In this essay I am going to examine the possibility of perceiving collapse as a spectre (or a ghost or an absent presence), which infers unhealed intergenerational trauma that needs to be tended to, as well as the possibility of making the very notion of collapse into an Ancestor. Transforming a spectre or ghost into an ancestor is a process known as ancestralizaion. But before the key elements of this argument can be unpacked, I need to explain something of the perils and possibilities inherent within the contemporary collapse discourse, and how it hinges on how we come to understand and respond to two parallel, and now increasingly convergent dynamics.

The first is that for millennia many different so-called civilizations, occupying various parts of the planet, have been involved in a conscious process of trying to extricate humans (or at least a significant section of the species) from the natural world, in their attempt to finally conquer nature. Through this vainglorious attempt to cheat death, and in the process become all-powerful and all-knowing, big parts of the world have been re-created in their distorted civilizational projections. While these civilizations invariably have fallen short of their ultimate goal—to become Gods—they each have made numerous contributions to this inherently self-destructive project. The price, or shadow, of this deep and cumulative ripping of the human being apart from the fabric of the living world (the mother) is destruction, which manifests as climate chaos, mass-species extinction and the threat of ecosystem collapse.

In parallel with this long process of multi-civilizational separation from nature is the much more recent emergence and flourishing of European Empires: what Giovanni Arrighi refers to as ‘the long twentieth century.’ Presently, we are living through the decline and eclipse of the United States Empire, the Pax Americana which has ruled this big blue planet since the end of the Second World War. Through its dominant currency, massive military might and globalising processes, the US Empire has created the most destructive force humans have ever unleashed on the planet: neoliberal capitalism. The looming demise of US hegemony also marks the end of more than five centuries of European Imperial rule. What started in 1491 with la Niña, la Santa Clara and la Santa Maria setting off from the port of Palos in Southern Spain in search of an alternative route to India, has now come full circle and is intent on devouring itself.

Heeding Gramsci’s advice, I want to draw attention to the potential monsters (which I am calling a spectre) that have and are revealing themselves as part of the unfolding of collapse. When cultures and economies are stuck and caught-in-between the living and the dead, precisely what a ghost is, the imminent danger is not that monsters take form and reveal themselves as a response to what is happening, but rather that individuals and collectives avoid facing what is actually happening. By proposing that the very notion of collapse is a spectre, I am suggesting that we would do well to not avoid that which is being revealed. If history is any sort of guide, as Georg Hegel reminds us, what we learn from history is ‘that we don’t actually learn from history.’ So, in order to facilitate an imaginary process I want to draw into constellation—a lá Walter Benjamin in his mercurial essay ‘On the Concept of History’ (1940)—two distinct and often incommensurate traditions. The first is the historical materialism of Marx and the radical traditions he spawned, and the second is a form of (reconstructionist) Gaelic paganism, which I will address forthwith.

When I invoke the word Gaelic, I am referring to the linguistic/cultural triangle of places that in modern state-based parlance includes Ireland, Scotland and Iceland. The paganism or animist cosmology being referred to is not a whole or unbroken tradition. Indeed on the contrary, it has experienced no end of very deep and painful ruptures and eviscerations, due to a variety of factors including the coming and domination of Christianity, Viking invasions and settlement, the mass violence of British colonialism (primitive accumulation) and modernity. Consequently, this tradition, which of course includes numerous celtic languages, has undergone innumerable attempts at being marginalised, assimilated, demonised and outright obliterated. The two most notable forms of the latter are Oliver Cromwell’s scorched earth policies of 1649-1653 and An Gorta Mor, The Great Hunger of 1846-1853.

After and through all of this violence and dispossession and migration, what remains is just a myriad of fragments or shards of culture. But because of the tradition’s focus on place and story and the animate, her tendrils still reach far into deep time. The reconstruction of this (re)emergent animist cosmology draws on the insights of comparative mythology/religion/literature, revival and survival of Gaelic languages, as well as history and archaeology. Coupled with this is a focus on grieving and healing the collective wounds associated with intergenerational trauma. Thus, the project of reimagining a Gaelic animist cosmology fuses healing and knowledge production as well as mind, body and land. The massive granite stone ancestor that is foundational to an emergent Gaelic animism contains the insight: ‘the secret of healing lies inside the wound, which contains the medicine.’

In this essay, I want to examine the fecund and often vexing relationship between civilizational collapse and monsters—or more precisely ghosts —which tend to appear and make their presence felt in the human imaginary, as a way of avoiding the need to reflect on who we are, how we got here or what we have become. This dimension is of course what Carl Jung calls the shadow. To engage the shadowlands, I want to bring into a creative tension the constellation of Marxisms and Gaelic paganism, because they both offer crucial insights into how we can understand and respond to different aspects or dimensions of the absent presence that is collapse/ing. Central to this perspective is the insight that both traditions have ways of evoking, comprehending and channelling the role and power of the Ancestors. I want to suggest that it is only by developing a supple and nuanced appreciation of how the past informs and weaves together the present, that we can begin to perceive collapse as a spectre. And through this body-based shift in perception we can gain the skills necessary to heal and transform collapse from being a spectre in order for it to become an Ancestor. And through this process collapse can become a resource we can draw on and relate to—and potentially become a moment of initiation/transformation—rather than a dynamic that haunts and limits and eventually monsters us into oblivion.

Encountering the Ancestors

In preparing to approach, make contact and communicate with Ancestors, and the wisdom that this relationship implies, I wish to iterate that all human traditions and societies have deep animist roots. Consequently, rather than being alien from or haunted by an animist cosmology, this observation points to our deepest animal nature which lies in the very substances that constitute our muscles, breath and blood. Moreover, Ancestors don’t need to be in human form, and this is where the notion of totemism comes in. While these observations may not be apparent or accessible for some, the Ancestors are always present and available—they inter-are.

In creating a space to encounter the Ancestors, let us first turn one of our faces towards Marx and the many Marxisms. Marx referred to his method as historical materialism, a method which takes the history of the doing and processes and organisation/s of our human ancestors very seriously. Transformative knowledge production, the locus of different forms of resistance and social transformation in the struggle for communism, is produced through engaging and winning the class struggle. To sharpen up your (and your class’) abilities and potentialities, this practice of social remembrance and transformation needs to be refined by reflecting on your experiences and that of your (class) Ancestors, and in the best case scenario, being utterly transformed through this encounter with the Ancestors. Marx, of course, is a central and very important Ancestor to this tradition. His grave in Highgate Cemetery, London is a revered site of pilgrimage for followers and fellow-travellers. If you visit his grave you might like to sing a revolutionary song, such as ‘Joe Hill:’

‘I dreamed I saw Joe Hill last night,

Alive as you and me,

Says I but Joe you are ten years dead,

I never died says he,

I never died says he…’

The Ancestors may be known by different terms in the left: martyr, freedom fighter and the like, but they are never far away. What I am uncovering is that at its deepest ontological level, Marxism is a secular and human-centred form of Ancestor veneration and worship. This is very much a strength of the tradition, and one of the reasons for its incredible endurance. For as Walter Benjamin reminds us: ‘What drives people to revolt are not dreams of liberated grandchildren, but memories of oppressed ancestors.’

Within most Marxist (and Anarchist) activist and academic circles such observations as the one I just made are heretical, and will likely lead to banishment and exile. But of course, this does not mean they are wrong. Part of the reason I offer these observations is to demonstrate that the very notion of Ancestors is a deeply rooted quality at the very core of our being. This is actually not that difficult to comprehend, because our Ancestors are always close to us, even closer than our own breath. We just need the faculties to see and listen and engage with them. Returning to Marx, the very first line of the Communist Manifesto offers the insight that ‘A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of Communism.’ The question could be asked by an astute observer; why is Marx, in such a foundational text, in its very first line no less, invoking ghosts? Ghosts are most completely understood within an animist cosmology as persons that have died and, due either to traumatic death, improper grieving, or something else unsavoury, were unable to transition into the Ancestral realm/the otherworld (there are innumerable ways of framing and naming these realms). They thus remain in this world, haunting and taunting the living.

For Marx—a Jewish person from a long line of Rabbis—the spectre or ghost is not a human person but rather the collective desire for liberation. The collective desire that Marx alludes to has, within modernity, deep roots in the Judeo-Christian traditions through the stories of the covenants and the prophets, and even deeper roots stretching back to our hunter/gatherer ancestors, which in the Marxist literature is referred to as primitive communism. While this sort of discussion may be confronting or destabilising for increasingly rootless cosmopolitans in and from the so-called West, in Latin America this dialogue between various liberatory movements and various Indigenous animist cosmologies has been ongoing since the conquistadores first invaded the Americas in 1492.

Ancestors in a Gaelic cosmology

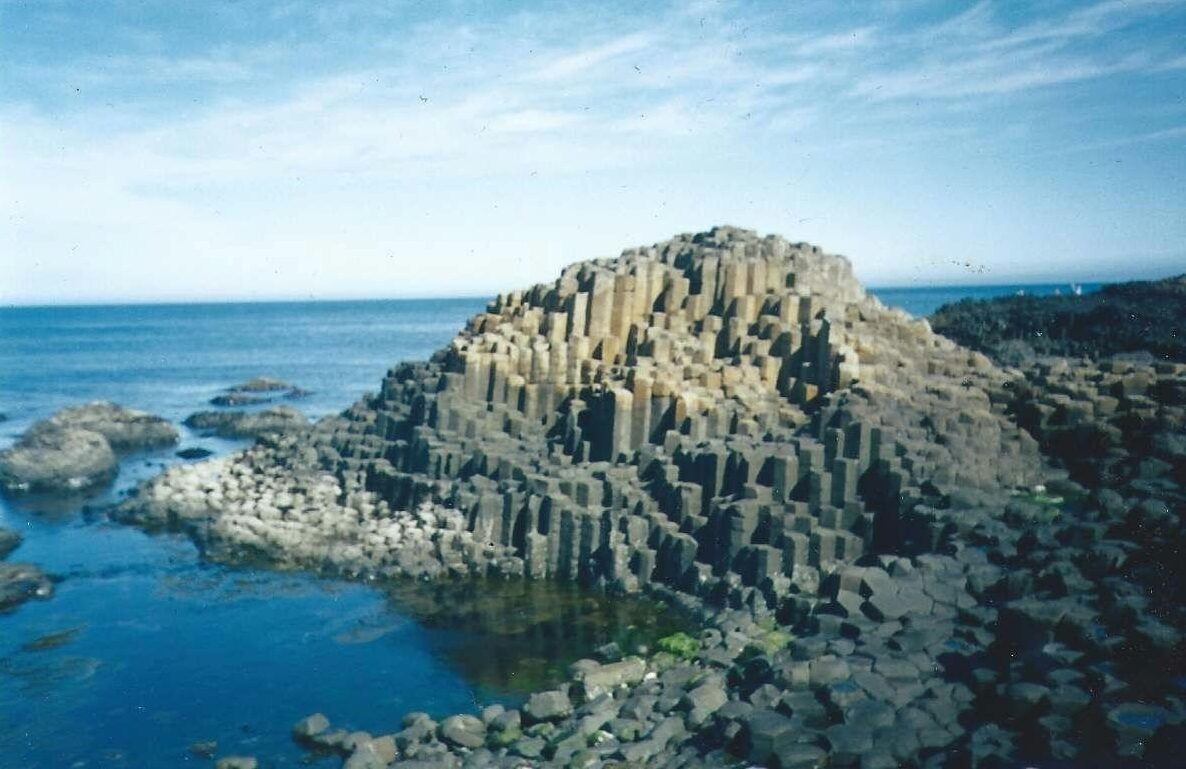

In the animist cosmology of the Gaelic worlds, Ancestors are in the same realm and often as important as, or even more important than, goddesses and gods. In this cosmology, the goddess—in her various forms—is the land, and takes various shapes including the land, various mountains, rivers, oak and other groves, ravens, cows and calves, old women or crones and young maidens. The Ancestors are often associated with the Si, the ancestral mounds, which can be where the literal blood Ancestors, as well as the more broadly understood (tribal, cultural, totemic) Ancestors dwell. Standing stones, stone circles, portal tombs and passage tombs (wombs) can also be powerful sites where Ancestral knowledge is accessed/kept/can be received through initiation.

In English, the Banshee is a woman who is a harbinger of death to be dreaded and feared, but in Irish, the Bean Sí is the woman of the (Ancestral) mound. Her role, and this can differ slightly from place to place, is to contact and work with the Ancestors, which is a term subsumed in the expression the dead in the Gaelic context. Living in an animist cosmology, where everything is alive and has a voice, the role of the Bean Sí is to communicate and work with the dead and the Ancestors. In other words, the Bean Sí has a range of shamanic and healing powers and, subsequently, she has an important role in the community. Of course, through time, this role and its implications are distorted and disfigured to suit the interests and language of whatever regime has control. In this very brief explanation, I have taken Sí to mean ancestral mound, but in much of Gaelic oral and written folklore and history, the Sí is more commonly associated with fairies and the fairy mound. Numerous learned folk have pointed out that the substitution of fairy for ancestral mound was a conscious colonial strategy undertaken in the 17th and 18th centuries aiming to subjugate an Indigenous population and its cosmology.

Ancestors give you a direct link to the living breathing cosmos and through that the profound mystery of life, death and rebirth. This said, not all your blood relatives are Ancestors. Some of them may be spirits of place or protector spirits rather than becoming Ancestors. Others, as already mentioned, may not have been grieved properly, or met grisly or traumatic deaths and have stayed in this realm as ghosts or absent presences, and never actually become Ancestors. Other blood relatives may have been sorcerers or have broken important social taboos or the like, and are not really suitable to be Ancestors.

A person that has not become an Ancestor has instead become a spectre, stuck in a certain realm or state, unable to move or change. I offer this prism as a creative way to view the narratives and seemingly this-worldly expressions of social and ecological breakdown/collapse. I am suggesting that the very notion of collapse is itself a spectre that is haunting us. In other words, because of the legacies of colonial violence, (it is of course far more complex than this, but for brevity I am choosing a very particular type of spectre and Ancestor) there have been/are/and will be numerous forms of social and ecological collapses: Cromwell’s scorched earth policies of 1649-1653 in Eire and John Batman’s ‘treaty’ with Kulin elders on the edge of the Merri Creek in ‘Melbourne, Australia’ spring immediately to mind. In other words, the threat of ecological and social collapse, is revealing to so many of us that previous collective Ancestral traumas have not been grieved properly or properly storied and still need to be tended to. Not surprisingly these traumas are coming to the fore, haunting how we understand and relate to what is happening in the now. The fundamental offering of this essay is this: those who are able to grieve and heal the intergenerational trauma of their Ancestors, are best prepared to comprehend and respond to the contemporary context of collapse.

Understanding and healing intergenerational trauma

Sadly, when we turn our face in this direction, there seems to be very little understanding, let alone insight, about the workings of or ways we can grieve and heal intergenerational trauma. In this space there is very little concrete comprehension of the nature of the wound, let alone its healing. Into this maelstrom, and rooted in Gaelic history and contradictions, I want to suggest that in order to understand and heal traumas that are transmitted through the generations, we need a collective and animist project. In sharing this insight, I am not attempting to make a universal comment, but I do suspect other colonised peoples can learn from each other. In other words, it is the very nature of the wound that reveals the medicine.

When intergenerational trauma is evoked, what exactly is the wound? When Cromwell’s New Model army ripped their way across the lands of Eire, was it just human persons that were (and still are) affected? What about the massive oak forests? The bog ecosystems? The boar and wolf and deer peoples? And the destruction of the stories and storytelling traditions that bound people, land and Ancestors together? What about the obliteration of ritual spaces where the stories were/are held in the land, and where important initiations and rituals were conducted? In the Gaelic context, the workings of intergenerational trauma are not just in regards to the legacies of mass violence of dispossession, massacre and genocide, but also very much about the destruction and severing of a people from a living breathing cosmology. This severing also includes a cutting of the umbilical cord to your Ancestors, and the sites of remembrance of these ancestral connections. This is why any attempts at healing intergenerational trauma in the Gaelic context need to have vital collective and animist elements, because that is part of what the wound looks and sounds and smells like.

Native American psychotherapist and traditional healer Eduardo Duran refers to intergenerational trauma in the context of Native communities on Turtle Island as ‘a soul wound.’ He makes this observation steeped in the insight that although the etymology of the word psychology evokes the notion of tending the soul, in the western articulation of psychology, soul is but the faintest of echoes, rarely encountered, let alone engaged or touched. In the Gaelic context, the severing from land and language and story is also a type of soul wound, but I suspect, at its deepest level, is a profound and painful severing from the land/mother/goddess.

Like Gaelic goddesses, the intergenerational wound also has three faces or aspects. The first face, I will suggest, is associated with the human persons, which is associated with widespread dispossession, enforced migrations, language destruction, innumerable massacres and bouts of great hunger. In short, it relates to the legacies of colonial violence. The second face is to do with the severing from the land: the realms of the non-human persons as well as the more than non-human persons. The ecological devastation wreaked upon forests, rivers, and animals, and the realisation that humans and place/non-human nature are not separate. The land is also hurting, and she needs tending and healing. This is where the potency of an animist cosmology is once again revealed. The third face is the severing from the gods and goddesses, trickster spirits and the Ancestors. This realm is very much about the destruction of story and language and how human communities are woven into the land and the cosmos through stories. In other words, addressing the cosmological dimension of the intergenerational wound.

It is our connection to the Ancestors that can and will heal the wounds of intergenerational trauma. This healing requires us to have a strong and growing relationship with the Ancestors, allowing us to be in the land, listen and respond to what is happening, and be able to open and contain healing spaces in the land, where the healing the Ancestors deem necessary and possible can happen. The severing of human persons from the Ancestors contained and living in the land is central to the inter-generational wound. Consequently, it should not be surprising that it is central to encountering and healing the wound. Just to reiterate, and to talk in spirals rather than straight lines, it is not humans in any direct way that frame or contain the healing of intergenerational trauma; this is the role and providence of the Ancestors. The human role, at its very best, is to help create the spaces and conditions where these encounters can occur, and as much as possible to hold and contain and to trust, not to know or do.

Story and storytellers role in healing inter-generational wounds

‘Tir gan teenga, tir gan anam.’ / ‘A country without a language, is a country without a soul.’ Pádraig Pearse

In the cosmology of Gaelic animism, stories are essentially the land speaking. Stories in this traditional context bind humans and the land, with its many features and persons, and the Ancestors together into a cosmological whole. In the corresponding social order, the role of the fili, or poet/seer, was to re-member, share and create stories and songs and poems as the need arose. The poet/seer was an advisor to the (clan-elected) King, who every year had to symbolically ‘marry’ the goddess (the land) in order to ensure the fecundity of the land. Because of the fili relationship to the King, they held a powerful position in the Gaelic world. Generally, the tradition of the fili was passed on through families, and each family ran schools to train and transmit their knowledge and wisdom. The fili was essentially a pagan role, their institutions were largely able to be accommodated within a Christian order, and they were not actually destroyed until the waves of Tudor and Cromwellian mass violence crashed across the lands of Eiru in the early to mid-17th centuries. Circling back to my previous discussion of Marxisms and the central role Ancestors play in resisting oppression, Dáithí Ó hÓgáin reminds us that filid (plural of fili) were central to building and sustaining the resistance to the British Imperial order, and were targeted for extermination, accordingly.

My sense is that fili and the schools of learning they sustained are returning, and they will be central not only to healing the wounds of intergenerational trauma in the Gaelic context, but also adroitly addressing the spectre that is collapse. At one level, the very best of western psychology is correct when it observes that trauma is an experience of the mind/body that the individual cannot integrate into their story. Collectivise this comment so it is about collective trauma and healing, and the central role of the fili is revealed. Healing intergenerational trauma is at root about unveiling a collective story, steeped in an animist cosmology, that can contain the trauma—and its many painful and powerful contradictions—as they are released from our collective (and Ancestral) bodies.

The final offering I want to make in this essay relates to the word curragh, a traditional type of boat made from cow hides and used extensively in the traditional Gaelic world. I want to suggest that stories being referred to in the context of a Gaelic cosmology are essentially curragh, containers that link us not only to the land and the Ancestors but also can hold us in deep waters—as we encounter the wild seas/massive sea creatures—that are inevitable in our individual and collective journeys. Stories are a curragh: especially when times are rough, when forms of social and ecological collapse are on the horizon, when various monsters are making an appearance. Curragh as a metaphor is a gift from the Ancestors, and it is because of their deep connection to the Ancestors that fili know how to work with a curragh. To unveil another layer of the word curragh, this whole discussion, as well as the imagination that informs it, dreams and feels and thinks about it mostly in English, and this is a part of the inter-generational wound. Central to collective healing, to the reimagining of the role of the fili and their schools, is the reclamation of the Gaelic language/s. It will help us to reconnect with the Ancestors and in turn find our way to our ait dúchais/native place.

Coming full circle

This essay attempts to creatively respond to numerous vexing issues associated with the uncertainties, deep confusions and sheer destructiveness associated with living in apocalyptic times. In making explicit the connection between the (mis)readings of the apocalyptic and social and ecological collapse, I contend that the long historical processes that constitute key aspects of the collapse dynamic are not only self-destructive, but also potentially contain transformative, healing and liberatory elements. This argument is substantiated by placing Marxism and Gaelic animism into a common orbit, and in so doing, drawing out the often understated animist and Ancestral roots of both traditions. Suitably equipped with an animist cosmology. I then make the claim that the very notion of collapse is actually a spectre, which is unhealed collective trauma. Moreover, a powerful way to respond to this observation may be to turn the very notion of collapse into an Ancestor, and in so doing facilitate the collective healing of trauma, which I suggest, necessarily entails the reimagining of traditional place-based storytelling traditions. Undertaking this sort of transformative/healing process, in a potentially apocalyptic/collapsing context, will I suspect also help us together make resilient story-communities, which are able to respond creatively, come what may.

- Thanks to Séan Ó Séaghdha, my Irish teacher, for help with translating this sentence. ↑

Colm McNaughton lives and works and dreams on Wurundjeri Country.